The story of the bird named “Little Eggplant” began in an unfortunate, but not unusual manner. This particular bird, a black kite, was found nearly dead in an eggplant field somewhere in Pingtung County. Since 2010, the Bird Ecology Lab at NPUST’s Institute of Wildlife Conservation has received black kites which were found injured or dead on 30 occasions; and of these, 24 cases (80%) were diagnosed as poisonings. Only seven of these birds were nursed back to health— with Little Eggplant among survivors.

In 2011, the Bird Ecology Lab began exploring the issue with support from Forestry Bureau and Pingtung County Government. It was at that time that the researchers learned that the problem could be traced to fields where farmers were using poisons to prevent crop damage from rats and sparrows. Efforts were quickly made to bring attention to the situation and help prevent further harm to Taiwan’s raptor populations. The details of these efforts are provided below, but first, back to the story of Little Eggplant.

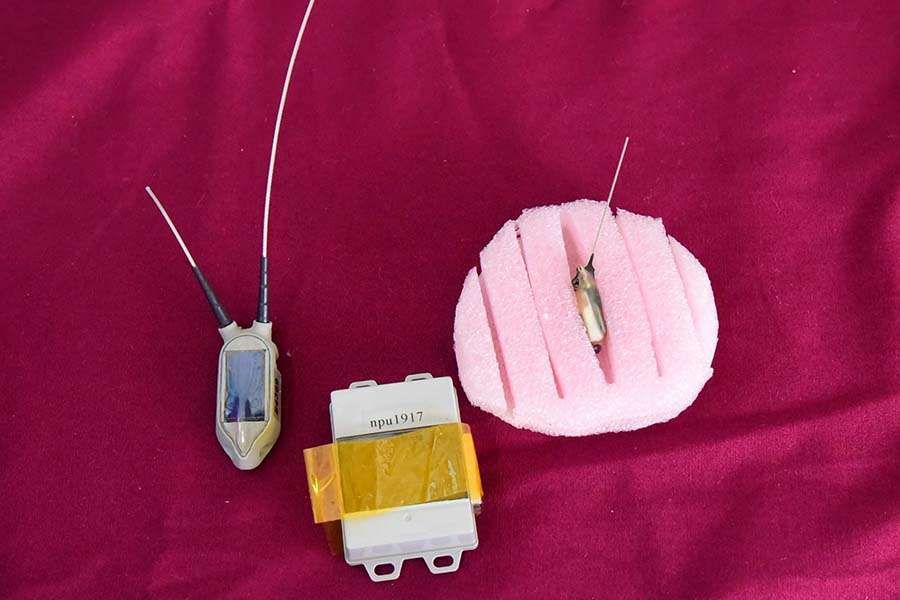

When the ailing bird was found in February of 2020, NPUST veterinarian Xenia Yin diagnosed it as a poisoning and administered an emergency dose of antidote. For the next several months the Lab caringly nursed Little Eggplant back to health, and when her strength had returned, they knew it was time to release her back into the wild. To conduct follow up observations, the team equipped the black kite with a GPS tracking tag before bidding her farewell. But shortly after, Little Eggplant’s story took an interesting turn.

One week following release, on May 5th, Little Eggplant unexpectedly and very suddenly made a one-day, 260 kilometer trip north, departing from Pingtung and flying all the way up to Yilan through the central mountain range at an altitude of 2500 meters (8200ft). This remarkable event set a record for the longest and highest flight of a black kite witnessed in Taiwan; and it also destroyed the notion that the black kites of northern and southern Taiwan have no dealings with one another.

Nevertheless, this black kite’s journey had only begun. On May 8th, early in the morning, Little Eggplant departed from the Fugujiao Lighthouse on the north coast of Taiwan and flew another 200 kilometers over the ocean before landing on an uninhabited island off the coast of Wenzhou, China. In the past, researchers had hypothesized that Taiwan’s black kite populations did not only consist of resident birds, and now it was very much confirmed.

Back in Pingtung, the researchers were carrying on with their conservation work. Huei-Shan Lin and Shiao-Yu Hong, two members of the Bird Ecology Lab, are dedicated to black kite conservation and have been promoting the adoption of agricultural practices which are friendly to raptors. Under the direction of Professor Yuan-Hsun Sun, these young bird enthusiasts have been working on a biological control method that is based on the natural food chain. They have learned that by setting up bird perches designed to attract black-winged kites, which are dedicated consumers of mice, they can establish field patrols. The first perches started going up in 2018, and already they are receiving positive reports. The Wufeng Farmer’s Association in Taichung, for instance, is finding the method quite effective— and they are even using the practice to promote a new brand: “Black-winged Kite Rice”.

The work of these conservationists also won them the 2020 Global Views Magazine University Social Responsibility (USR) award in the “Good Ecology” category. Professor Yuan-Hsun Sun explained that “everyone on our team has a passion for raptors— and through our research, we hope to gain a better understanding of their world. When we realized that there was a conflict between raptor conservation and agricultural practices, we began working to help farmers understand the important role wild animals in play in the ecosystem, and how they can be “partners” which can actually do a service for the farmer in their fields.”

NPUST President Chang-Hsien Tai commented on the achievements, explaining that “at NPUST there are many teams silently working away on issues related to environmental sustainability. The team at the Wild Life Conservation Institution is an important part of this work. The university is serving as a think tank; and in addition to rescuing and caring for animals, they are surveying ecosystems, tracking animals, and helping all sectors to understanding that conservation starts with individual awareness.”

Though it is still not where it needs to be, this awareness has already come along way. Through their literature reviews, members of the Lab learned that in 1980, agricultural departments began teaching farmer’s to spread grain mixed with Carbofuran at the edges of the fields to prevent crop damage from birds. At the same time, they also began holding a nation-wide “rat extermination week”— while providing free rat poison to the farmers. As a result, black kites, which are scavengers, became indirect victims of the poisonings. In the 10 short years that followed, populations saw sharp declines with very few people taking notice. In 1991, people finally began tallying the numbers, only to find that that the birds had nearly been brought to extinction— with only 200 remaining in Taiwan.

After realizing “why” the Black Kites were disappearing, Professor Sun and his two researchers began discussing the problem with the Bureau of Animal and Plant Health Inspection and Quarantine, which recognized the need to respond. Consequently, the Bureau brought “rat extermination week” to an end and, in 2017, they also placed a ban on the use of Carbofuran pesticides. Nevertheless, the harm to both birds and rats had still not been fully resolved, and so, in the same year, the Lab launched the “Birds of Prey Biological Control Method”, whereby perches were erected in open fields to attract black-wing kites and collared scops owls— both of which are accustomed to resting on high perches. In their latest research they also realized that the two different birds prefer to perch at different heights, and so they redesigned the structure to include two different levels, with a 4 meters rung set for the collared scops owl and a 7 meter rung for the black-wing kite. And since the birds operate on different shifts, the installments can serve their purpose round the clock without any disputes over turf.

As for demographic trends, according to an annual nation-wide black kite survey conducted by the Raptor Research Group of Taiwan, black kite populations are on the rise— with the latest stats from 2019 putting the total at 709. These birds, however, are still limited to the north and south ends of Taiwan, with no stable populations in central or eastern parts of the country. In recent years, the increase in numbers demonstrates that the poisoning threat has come down since 1980; however, there is still room for improvement.

And as for Little Eggplant: from the time she landed in China, she has continued travelling north at between 100 and 250 kilometers per day and by May 17th, she had already travelled 1600 kilometers from where she had been released. The researchers at NPUST send her their blessings and hope to see her make a smooth return trip this fall to the place where the journey began. In the meantime, they will continue to follow her story as she teaches them about the full extent of the migratory black kite’s journeys. Sustainable development is an issue that people from every area of study need to make an effort on, and hopes are that Little Eggplant’s inspirational story will help raise awareness and promote the vision for friendly farming practices which strike balance between agricultural activities and the ecosystem conservation. NPUST’s mission is to cultivate professional agriculturalists, and continue with each field of study promote sustainable activities around the world.